Pitfalls and Perils of Disease Screening

Detecting early treatable disease is medicine's holy grail, we just need to find the sweet spot

Dr. Larry Istrail is the author of The POCUS Manifesto: Expanding the limits of our physical exam with point-of-care ultrasound. You can get a copy here or watch his grand rounds lecture here.

—

“The right to protect the health and well-being of every person, of those we love, is a basic human right…Yet in the United States today, healthcare is the leading cause of bankruptcy and the lack of it the leading cause of ... finding out too late in the disease progression process that someone you love is really, really sick."

- Former founder of Theranos, Elizabeth Holmes

I had the privilege to attend TEDMED in 2014 as a medical student covering the conference for MedCrunch, an online med/tech magazine. Like Bill Clinton, Henry Kissinger, Walgreens, and the most prominent venture capitalists in the world, I was enthralled (and duped) by a new blood-testing company called Theranos that claimed to provide accurate blood tests from a drop of blood. Their conference booth was a beautiful and modern contrast to the traditional stale lab aesthetic, and they were offering free finger-prick cholesterol screenings. They warmed my fingertip to dilate the blood vessels, pricked my finger, sucked up a couple of drops of blood into their “nanotainers,” and within 24 hours my cholesterol level appeared in my iPhone app. The process was incredibly cool, seamless, and enjoyable. There is just one problem: it was probably all fake.

Elizabeth Holmes checked all the silicon valley boxes for the next unicorn founder: pathological determination, quirky behaviors, black turtleneck, vegan juicer, and Stanford dropout. She had a curiously perfect back story combining fear of needles and an early death in the family (that we later learned was manipulated and/or totally made up for effect). This all propelled Elizabeth’s vision of democratizing blood testing to enable early detection and prevent devastating, late diagnoses.

What I didn’t appreciate at the time, and what makes the Theranos story even more confusing, is that the Edison Device she was claiming to invent essentially already existed.

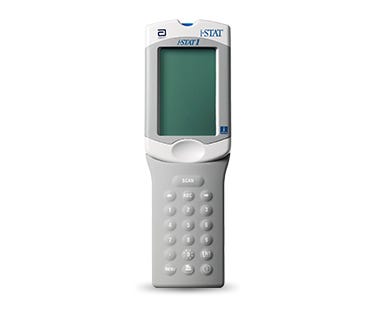

While she was faking investor presentations or using unapproved pharmaceutical company logos on her documents to give Theranos some street-cred, the Abbott Piccolo Xpress already offered a similarly sized, touch-screen-equipped, modern-looking blood testing machine that can perform 31 blood tests on a 0.1 cc of blood (about 5-10 drops) in only 12 minutes. Or the iSTAT handheld machine we use in the hospital that can provide accurate results on a handful of markers with just 2-3 drops of blood.

More testing: not always better and often worse

The hypothesis that screening healthy people prevents severe disease is an intriguing one. It is, after all, why we have annual physicals, mammograms, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing, digital rectal exams, apple watches to detect abnormal heart rhythms like atrial fibrillation, or pap smears. It is a tantalizing oasis of simple detection in the messy biological desert of disease. And like many oases, they don’t actually exist when you take a closer look.

The Cochrane Collaboration found, for example, that the annual checkup at the PCP “did not reduce morbidity or mortality, neither overall nor for cardiovascular or cancer causes, although the number of new diagnoses was increased.” This conclusion was from their review of 16 clinical trials including over 180,000 subjects. Dr. Ezekiel Emmanual wrote a New York Times piece on this titled “Skip your Annual Physical,” bluntly stating that:

“Regardless of which screening tests were administered, studies of annual health exams dating from 1963 to 1999 show that the annual physicals did not reduce mortality overall or for specific causes of death from cancer or heart disease. And the checkups consume billions, although no one is sure exactly how many billions because of the challenge of measuring the additional screenings and follow-up tests.”

This lack of evidence is why the United States Preventative Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend annual physicals, and why, for example, the Canadian guidelines recommend against them, as they are “not supported by evidence of effectiveness and may result in harm.” Nevertheless, they still remain common practice for many reasons including habit, a sense of controlling your medical destiny, and of course, a way for primary care doctors to get and maintain patients.

This lack of benefit, at least to some degree, may result from the fact that we are using medieval screening devices with extremely poor ability to detect disease to begin with, even when the patient is symptomatic. In a large study of patients diagnosed with congestive heart failure (CHF) for the first time in a hospital setting, 1 in 6 of them had heart failure-related symptoms such as edema or shortness of breath documented during outpatient clinic visits in the 6 months prior, suggesting they were likely in heart failure already, it was just not detected. This makes up about 170,000 patients who had symptoms yet the diagnosis was not made with standard means. With the replacement of a stethoscope with an ultrasound in the hands of a point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) trained clinician, these patients would have been detected immediately and appropriate care started on time.

Screening for Melanoma

Along the screening to diagnosis spectrum, if we venture too far towards the unnecessary screening side we can cause a lot of harm through unneeded testing, complications from biopsies or new medications, or from creating a pipeline of cancer patients that don’t actually have cancer that needs treatment. The latter was brilliantly illustrated in a recent NEJM article on the rise of cutaneous melanoma, a cancer that starts in the pigment-producing cells of the skin and results in 10,000 deaths a year. However, it has a 98% survival rate if caught early which makes it a great potential candidate for early screening.

Once a rare diagnosis, it now is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in the United States, yet disagreement surrounds whether this increased incidence represents “an epidemic in the true occurrence of disease,” or “an epidemic of diagnosis.” If the screening test is doing its job, it should detect early disease and prompt early treatment that reduces the incidence of severe disease, thus reducing melanoma-related death.

Yet this is not what we see.

The incidence of melanoma is now 50 times as high as it was in 1975 (25 vs. 0.5 per 100,000 population) while “the rising detection and treatment of melanoma in situ has failed to reduce the incidence of invasive melanoma, which increased from 7.9 to 25.4 per 100,000 population over the same period. The lack of any appreciable effect in reducing the occurrence of invasive melanoma suggests that melanoma in situ is not a regular precursor — much less an obligate precursor — of invasive melanoma.” (Figure A below)

In addition, the mortality from invasive melanoma has been stone-cold steady while the diagnosis incidence skyrockets (Figure B). Stable mortality, the researchers argue, “should be viewed as a marker for stable true cancer occurrence; thus, when accompanied by steeply rising incidence, the pattern should be viewed as pathognomonic (i.e. indicative) for overdiagnosis.”

Because of this, the authors - a dermatologist and a pathologist - recommend against population-wide screening for skin cancer, as this results in a 6X increase in diagnoses with no apparent effect on mortality. Similar negative results were seen with prostate cancer screening, screening for atrial fibrillation, or even mammograms for breast cancer, that had this sobering summary in a Cochrane review:

If 2000 women are screened regularly for 10 years, one will benefit from screening, as she will avoid dying from breast cancer because the screening detected the cancer earlier.

At the same time, 10 healthy women will, as a consequence, become cancer patients and will be treated unnecessarily. These women will have either a part of their breast or whole breast removed, and they will often receive radiotherapy, and sometimes chemotherapy.

Furthermore, about 200 healthy women will experience a false alarm. The psychological strain until one knows whether or not it was cancer, even afterwards, can be severe.

The world of mammography is a fascinating one in which scientific findings, political debate, and screening advocacy have often butted heads in ugly ways.

Screening that works

For a screening test to work, it must have a high sensitivity (detect majority of cases) while ideally having a non-invasive, quick, and easy way to rule out false positives. Usually this requires a biopsy, though POCUS is changing things. Since POCUS often allows for direct visualization and diagnosis of diseased organs rather than the measuring of a surrogate, it is an optimal screening device. It can be done at the bedside and provide immediate answers with a handheld device that is becoming increasingly affordable. This was highlighted beautifully in a study of high school and college students being screened for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), a rare but highly fatal disease that often manifests as sudden cardiac death in young athletes.

It occurs in approximately 1 in 500 people, suggesting about 600,000 people in the U.S. have it. The only reliable way to diagnose it is with an echocardiogram, but this requires a trained echo technician to perform the study and a cardiologist to interpret it. Given these limitations, these physicians in this study opted to train medical students in basic cardiac ultrasound to show that with point-of-care ultrasound and a medical student, HCM can be adequately screened for.

The students were trained to obtain two cardiac views and measure the interventricular septum(IVS) to left ventricular posterior wall thickness ratio. A ratio greater than 1.25, or a left ventricle > 12mm thick was considered abnormal, and those with an abnormal screen then underwent a standard echo with a cardiologist.

They scanned 2,332 students and 137 were found to have a positive screen. Of those, seven were confirmed to have HCM. There are young people that would otherwise not have been detected, potentially saving their lives from future sudden cardiac death. The students with a positive screen who did not have the diagnosis only required to undergo an echocardiogram as a confirmatory study, as opposed to a biopsy or other invasive measure. This study was limited by the fact that they didn’t do a standard echocardiogram in everyone, but they clearly showed that a clinician with minimal training could perform a cardiac ultrasound screening test that could detect life-threatening disease.

Elizabeth Holmes was found guilty and just about everything about her - from her company’s capabilities to her baritone voice turned out to be a fraud. Her dream of detecting early disease from a finger prick of blood is a laudable one, though not one based on scientific evidence. On the other hand, point-of-care ultrasound offers immense opportunities for screening tests to be reinvented, and make annual physicals relevant once again.

—

Dr. Larry Istrail is the author of The POCUS Manifesto: Expanding the limits of our physical exam with point-of-care ultrasound. You can get a copy here or watch his grand rounds lecture here.