Dr. Istrail is a physician and author of The POCUS Manifesto: Expanding the Limits of our Physical Exam with Point-of-care Ultrasound

If the stomach had a catchphrase, “silent but deadly” might be it. Especially from the perspective of a fresh carrot. As that crunchy orange nature candy is jettisoned down the esophagus, the stomach’s ultra-acidic juices start flowing in preparation for the pending carrot carnage. The carrot is churned and burned into tiny carrot particles and, in assembly line style fashion, gets peristalsed into the intestines for its nutrient acquisition phase.

The mucosa, or inner lining of the stomach, is equipped with acid-resistant cells that can handle this caustic, pH-of-2 fluid, and it can secrete acid-neutralizing lipids called prostaglandins. Yet if the mucosa is breached, this erosive body juice causes an ulcer by penetrating into the deeper stomach layers, damaging gastric tissue in its wake.

We take for granted the known causes of ulcers today. There is chronic NSAID use, like aspirin or Advil, that inhibits those trusty prostaglandins. Or Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) that infect the inflamed stomach lining.

Yet prior to 1985, an ulcer’s etiology was thought to be primarily psychological, appearing in the stomach after a major life stressor. While there is likely some truth to this hypothesis, no one believed bacteria could cause ulcers until one clinician made himself the subject of his own experiment to prove it.

This is a medical discovery story that heeds many lessons for today. As social media and government officials attempt to promote evidence-based information and suppress falsehoods (with many embarrassing missteps along the way, see: here or here for example), they must not forget the lesson of just about all of medicine’s great discoveries:

the misinformation of today may be the standard of care of tomorrow, and every new discovery - by definition - is either not known or even vehemently opposed - by the physicians and scientists of the time.

“Unidentified curved Bacilli”

In 1983, Australian Pathologist J. Robin Warren wrote into the Lancet describing curious findings of S-shaped bacteria present in the 135 gastric biopsy specimens he examined. “The extraordinary features of these bacteria are that they are almost unknown to the clinicians and pathologists alike … How the bacteria survive is uncertain.” The clinical significance was not known at the time, but he hypothesized that with so many bacteria clustering in inflamed areas of the stomach lining, these organisms “should be recognised and their significance investigated.”

Australian gastroenterologist Dr. Barry Marshall replied that he had cultured these bacteria and found they “do not fit any known species either morphologically or biochemically,” and that “the pathogeniticy of these bacteria remain unproven but their association with [white blood cell] infiltration in the human [stomach] is highly suspicious. If these bacteria are truly associated with antral gastritis, as described by Warren, they may have a part to play in other poorly understood, gastritis associated diseases.”

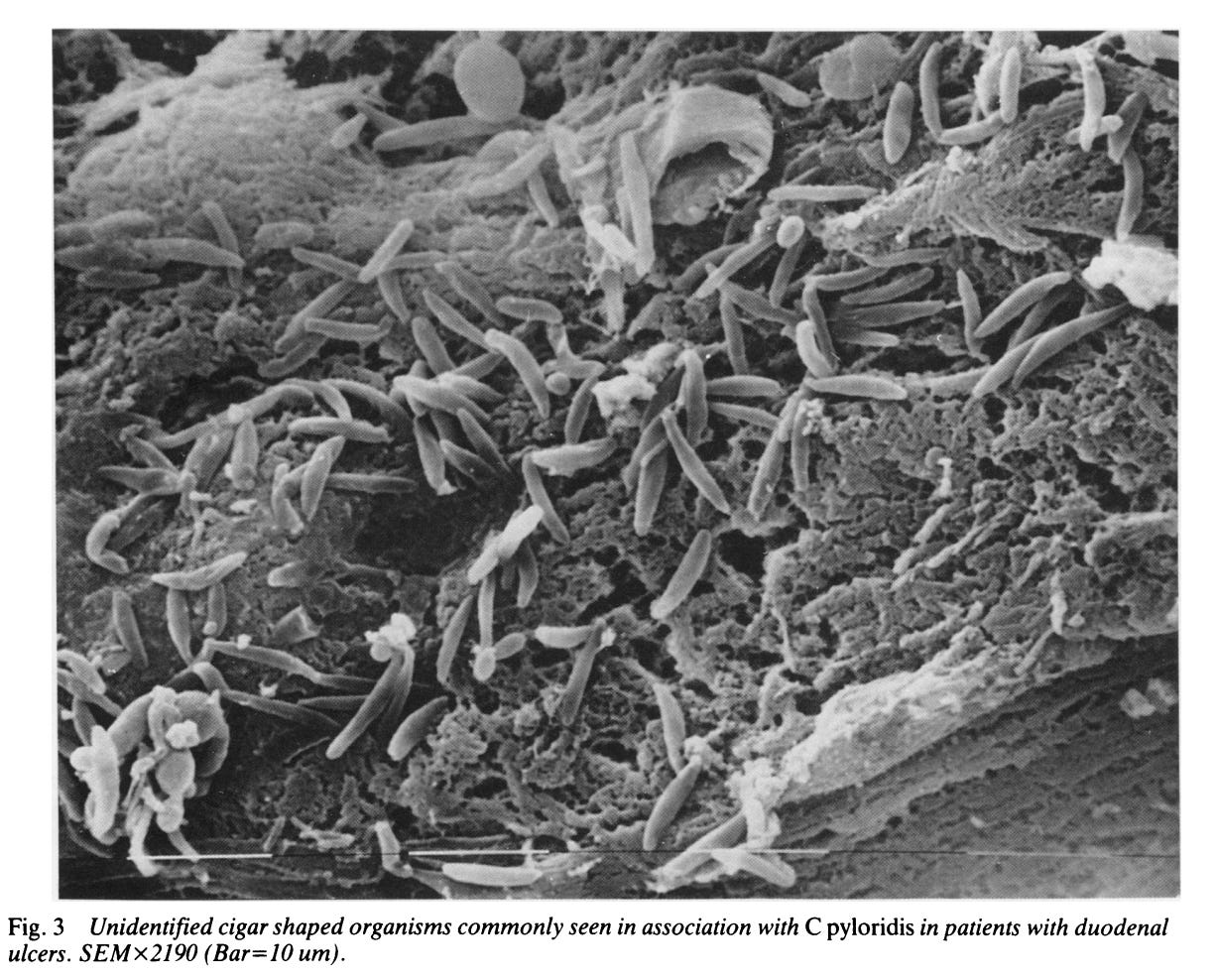

This organism was initially named Campylobactor pylori (or pyloridis), but the name changed to Helicobacter pylori in 1989. In follow-up studies, H. pylori was visualized with scanning electron microscopes (see image below) and found in the majority of duodenal and gastric ulcers. “At present,” the researchers from one study concluded, “one might tentatively suggest it is a marker in patients with gastritis at risk of developing a duodenal ulcer.” However, these bacteria were also present in some healthy individuals without gastric ulcers, confounding a direct causal linkage.

As a medical trainee, Marshall worked with Warren on a research project evaluating patients who were sent for biopsy for presumed stomach cancer, but in fact, found these mysterious S-shaped organisms instead. One of these people, a woman in her forties, had been a patient of Dr. Marshall. She was having nausea and stomach pain, but none of the standard tests were abnormal. “So of course, she got sent to a psychiatrist who put her on an antidepressant,” he explained in an interview. “When I saw her on the list, I thought, ‘This is pretty interesting.’”

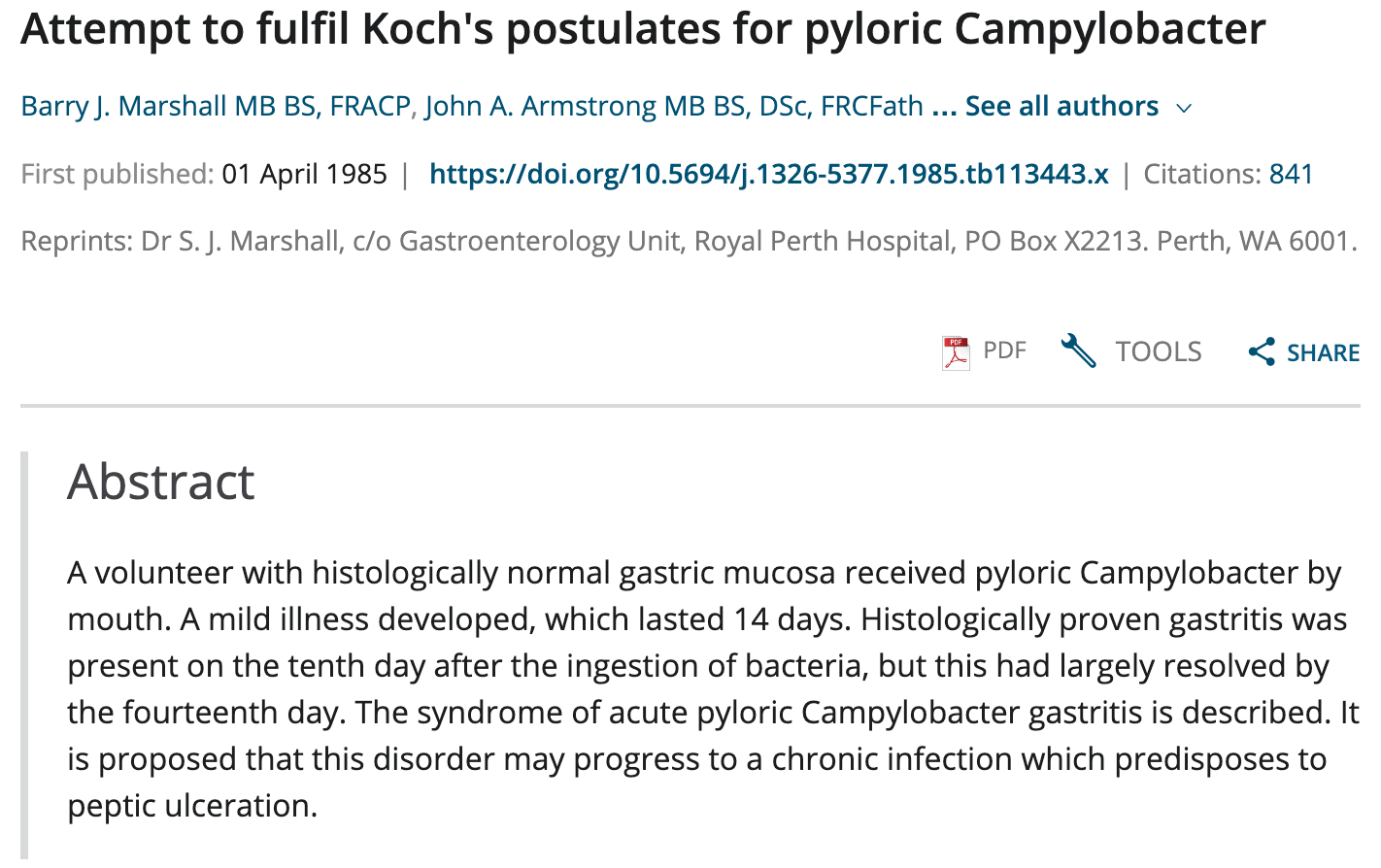

Marshall hypothesized that these bacteria were not just associated with inflammation of the stomach lining, but were actually causing it. However, he had no animal model that could prove it. And so, he took matters into his own… stomach. “I had been arguing with the skeptics for two years and had no animal model that could prove H pylori was a pathogen,” he explained in an interview years later. “If I was right, then anyone was susceptible to the bug and would develop gastritis and maybe an ulcer years later. So I expected to develop an asymptomatic infection.”

Dr. Marshall underwent an endoscopy in July 1984 to confirm that he was negative for H. pylori. He obtained a ‘brew’ of a sample from a patient with indigestion that had H. pylori (and was proven sensitive to antibiotics) and drank it.

“If only I knew that people would be so interested, I would have taken a photograph!”

After 5 days he started to have bloating and fullness, bad breath, and vomiting. His follow-up endoscopy showed severe gastritis with white blood cell infiltration and mucosal damage. “After 14 days, I repeated the endoscopy and then, before the results were known, began taking antibiotics (on my wife’s orders!) … The paper was published in the third person, but it gradually became known that the ‘male volunteer’ was me.”

Dr. Marshall presented his findings at the annual meeting of the Royal Australian College of Physicians in Perth, Australia to an audience that was less than receptive.

“To gastroenterologists, the concept of a germ causing ulcers was like saying that the Earth was flat … The idea was too weird.”

After they published their study, it was largely ignored for another 10 years before anyone would start treating ulcers with antibiotics. “I had this discovery that could undermine a $3 billion industry, not just the drugs but the entire field of endoscopy. Every gastroenterologist was doing 20 or 30 patients a week who might have ulcers, and 25 percent of them would. Because it was a recurring disease that you could never cure, the patients kept coming back. And here I was handing it on a platter to the infectious-disease guys.” The medical community was not convinced until Procter & Gamble, the makers of Pepto-Bismol, and their PR firm became involved. With some eye-catching newspaper headlines, Marshall’s work gained publicity. Other clinicians and researchers started investigating, and by 1993, “the whole country changed color.”

When asked how he felt new ideas could be heard when medical journals are gatekeepers of the status quo, Dr. Marshall replied optimistically. The journal reviewers “have their ears pricked up now because every time a paper comes to them, they say: ‘Hang on a minute, I had better make sure that this is not a Barry Marshall paper. I don’t want to have my name on that rejection letter he shows in his lectures.’”

Now they might say, ‘It’s so off-the-wall ... Is it true?’”

—

Dr. Istrail is a physician and author of The POCUS Manifesto: Expanding the Limits of our Physical Exam with Point-of-care Ultrasound.